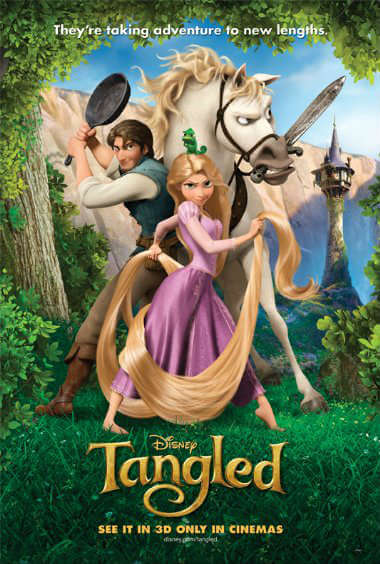

With its all-star cast, toe-tapping songs, and clever plot, Disney’s Tangled garnered quite an audience. The modern, adventurous take on the classic Grimm fairy tale made a whopping $591,794,936 worldwide, ranking it as the 87th highest grossing film in the world (1). That’s not too shabby if you ask me. So, what was it about this new Disney Princess and her captivating story that won the hearts of millions of people around the globe? How did Disney reinvent this simple tale of a maiden trapped in a tower into something that would enchant and feel relevant to modern audiences?

RELATED Behind the Fairy Tale: Maleficent

To start things off, I would first like to clarify that I will be focusing on the Grimm’s version of Rapunzel as the “original” influence in my analysis of the Disney version of Rapunzel. This by no means implies that the Grimm version is the actual original. It is simply a means of referring to the Grimm’s version without having to repeat the phrase “the Grimm’s version” every time I want to refer to them. Having clarified that detail, let’s begin our journey into these two very different interpretations of the same story.

The basis behind the story of Rapunzel, the girl locked away in a tower, is thought to be the legend of Saint Barbara, who was locked in a tower by her father for refusing a number of marriage proposals. The tale speaks to the prevalence in past centuries of women being treated as a sex that needed to be locked away and protected from roving young men. We come from a culture that regularly locked young women away in convents or at home in order to isolate them from society, segregate them from males, and police their behavior (2). Rapunzel gives a voice to these young women and brings to light the oppression, fear, and helplessness that goes hand in hand with this practice.

In the same vein, the tale deals with the issue of parents trying to delay the inevitable life cycle of adulthood and parental separation. However, the original tale doesn’t give much thought to how the heroine might gain control over her situation and her fate. Rapunzel escapes from the tower and eventually reunites with her prince almost entirely by chance (2). She is a slave to her fate rather than the ruler of it. Disney made the wise choice when making Tangled, to do some remodeling and give audiences a new and improved interpretation of Rapunzel.

Disney made a number of significant changes to the original story. The transformation began with its leading character, Rapunzel. Tangled doesn’t sport the demure, biddable, and passive heroine from the original Grimm’s version. Instead, we’re given a feisty, adventurous, and lovably starry-eyed young woman worthy of young girls’ admiration. The Rapunzel in Tangled is no push around. She proves to be quite the force to be reckoned with as we follow her on her quest to find the lanterns in the sky. This is a young woman who steps up and learns to claim her power as an independent and strong female heroine. Disney frees the passive and oppressed heroine from the original tale and gives wings to this once grounded female character. Thus, a new Disney Princess is brought to life to hopefully empower young girls and teach them how to navigate through the twists and turns along the way to adulthood, and escape their own tower and the adults that (probably with the best of intentions and feelings of love) might want to keep them in that safe enclosure forever.

Another major transformation Disney made to the tale is in the character of the prince, or in this case, thief, Flynn Rider. As with Rapunzel, Disney ditches the mostly passive and uninteresting character of the prince, turning him into a charming rogue, who makes his living as a thief. This character, who is also a slave to the whims of the evil enchantress, Mother Gothel, gains some much-needed gumption and attitude. Disney raises him from a rather weak victim of his circumstances to a hero actively engaged in the journey as well as the conflict present in his tale.

To top things off, this radical re-imagining of the lead characters leads to the final outcome of a far different example of male and female romantic partnerships. Both hero and heroine take an active role in confronting the obstacles they come across during their journey towards becoming mature adult partners, something you will see the original pair did not participate in. They form an equal partnership, transforming the outdated male-dominant/female-submissive romantic partnership present in the original version of the tale into a much more modern and enlightened relationship.

So, put your seat belts on and let me take you through a journey spanning centuries, in which I will demonstrate how Disney’s overhaul of Rapunzel’s key characters comes together to form a fresh, modernized take on this classic tale that has captured so many hearts.

The Evil Enchantress

The first major change Disney made to the Grimm’s Rapunzel was with its opening act, which explains how Rapunzel ends up locked away in a tower with the powerful enchantress Mother Gothel as her adopted mother. In the original tale, we are first introduced to Rapunzel’s birth parents. A picture similar to that of the Garden of Eden is painted for the reader. The mother and father in a most cavalier fashion trade their own daughter in order to gain the forbidden rampion from the enchantress’s garden. The mother is ultimately the culprit in this crime.

Mother Gothel, in comparison, is an example of the consummate overprotective parent, hiding Rapunzel away from the world (2). One has to wonder who is the worse parent. Rapunzel’s birth parents actions are certainly not those of loving individuals. Mother Gothel is almost justified in her demand for justice from the thieving pair, and it would seem that she is even saving Rapunzel from unfit parents when she demands the child as recompense for the stolen rampion. This certainly raises the question of how readers are supposed to interpret the figure of Mother Gothel. Is she an evil witch or a benevolent guardian? I don’t know that I would want to be left with parents who were willing to barter me away for some paltry lettuce. Mother Gothel sounds like a woman who perhaps wanted a child and found a way to get one through her dealings with these unfit parents.

Her containment of Rapunzel in the tower appears more like the actions of an overprotective parent desperately trying to stave off the maturation into womanhood of her daughter and the separation that comes with it. Ironically, Mother Gothel chooses to lock Rapunzel away in a tower, a clear phallic symbol hinting at the futility in Mother Gothel’s efforts to keep Rapunzel from reaching sexual maturity (2). But, while containment implies safety, it also inhibits the satisfaction of desires, which becomes the main issue of the story (2). This also affects how Rapunzel’s escape can be interpreted. Is it an act of betrayal or clever resourcefulness?

Disney does away with this tricky question by having Mother Gothel steal Rapunzel away from them in the night. The parents have no involvement in Rapunzel ending up as the adoptive daughter of Mother Gothel. Mother Gothel chooses to steal Rapunzel not out of a desire for a child but because she wants exclusive use of the magical properties in Rapunzel’s hair. Her vanity and desire to stay forever young are her less than pure motives.

As Richard Corliss states in his review of the movie, “Gothel knows the secret that many American parents act out but are slow to acknowledge: that confining their teens in enforced preadolescence helps them feels younger too” (3). This changes how we might interpret Rapunzel’s confinement. Disney paints a much more black and white image of Mother Gothel than the original tale, allowing the audience the freedom of placing her firmly in the bad guy category. Disney’s Mother Gothel takes the cake among their pantheon of evil stepmothers. A New York Times review labeled her as a “classic underminer,” stating that, “she has brainwashed Rapunzel into loving her, and her brutal selfishness is camouflaged in sweet-voiced expressions of solicitude” (4).

The mastermind behind the voice of Mother Gothel is highly acclaimed actress Donna Murphy. Not one to take a role lightly, Murphy came armed with “eight billion” questions about the character. Director Nathan Greno stated, “She wanted to know everything about the character before she started working: What was she like as a child? Had she been married? Did she grow up in the kingdom? Things we hadn’t thought about.” The result was an awe-inspiring performance. “She WAS Mother Gothel. Usually, you do multiple recording sessions with these kinds of characters. But she did it once through and most everything you hear is from that first session. We’ve never met anyone like her (5).”

One of the most notable differences between the two versions of Mother Gothel is how they chose to deal with Rapunzel’s rebellion. When Mother Gothel discovers Rapunzel’s plan to escape with the prince, she calls her a “wicked child” (2). This line is a key indicator of the mindset of Mother Gothel, particularly of her refusal to let go of the idea of Rapunzel as her young child. She is desperately trying to hold onto Rapunzel’s childhood self, refusing to acknowledge that Rapunzel is no longer a child. Ironically, it is, in fact, Mother Gothel’s fault that Rapunzel makes the unwise choice to deceive her. Mother Gothel has sheltered and overprotected Rapunzel, not giving her the tools to even know how to make a wise decision as an adult. Therefore, she cannot be wicked, as her decisions are coming purely from a place of innocence and lack of knowledge.

As punishment, Mother Gothel cuts off Rapunzel’s hair and banishes her to the wilderness. While this may seem cruel at first, when you consider her actions in the terms of her previous refusal to let Rapunzel grow up and leave the nest, they are actually rather kind in a “tough love” kind of way. Mother Gothel finally releases Rapunzel from her confinement, allowing her to mature into an adult woman, the very thing she was trying to prevent before.

Her treatment of the prince afterward can be seen as a form of revenge upon the person who ultimately stole her child away. She lures the man who took her daughter away from her into her clutches from a desire to hurt him the same way he has hurt her. She then proceeds to let him fall from the tower onto the brambles below, blinding him (2). Is she wrong? Yes, but I would argue that her actions are those of a grieving mother who doesn’t know how to cope with her daughter growing into an adult and starting her own life separate from Mother Gothel. This is an emotional trial that all parents must go through, and we see that played out in the Grimm’s version of Mother Gothel.

Disney takes the story in the complete opposite direction. This version of Mother Gothel seems less concerned with Rapunzel as her daughter escaping than the fact that she will lose access to her magic hair. Her response is calculating as opposed to emotional. She follows Rapunzel on her journey, placing doubts in her head in an effort to break her down so that she returns to the tower as a biddable and easily controlled slave. She manipulates Rapunzel into thinking that all Eugene wants from her is the crown and not her friendship. This gradual destruction of Rapunzel’s self-esteem comes to a climax when Eugene abandons her. All of the lies Mother Gothel has told her about herself and the outside world over the years burst to the surface and Rapunzel begins to believe that she is worthless and that the world is a dangerous, cruel place. Mother Gothel’s cunning manipulation appears to finally be winning against Rapunzel’s optimistic and curious nature. This version of Mother Gothel lets Rapunzel experience the wonders and beauty of the world outside and then cruelly snatches it away from her. I would suggest that this is a far more insidious and evil characterization of Mother Gothel than the Grimm’s. Disney’s Rapunzel has a much smarter and more evil foe to conquer.

The Maiden In The Tower

Disney’s more formidable foe also requires a stronger hero and heroine. While Disney’s Rapunzel is still innocent and sheltered, she’s been gifted with a few extra talents and tricks up her sleeve. In order to better understand them, let’s take a look at the Grimm’s Rapunzel.

Our first peak at Rapunzel reveals that she is “the most beautiful child on earth,” and that the enchantress uses her long golden tresses to climb up the tower and visit her (2). The fact that she has golden hair tells us two things. First, we know that she is beautiful. Secondly, we can deduce that she is a good person. We know this because golden hair in fairy tales is a marker of both aesthetic beauty as well as ethical goodness (2). The only other descriptive details we are given is that she has “a voice so lovely” since it this voice that draws the prince to her tower, and that she is isolated and lonely in her tower. When the prince comes upon her, she is “all alone in the tower, passing the time of day by singing sweet melodies to herself.” Then when she first sees him she is frightened “especially since she had never seen one (a man) before (2).” That’s about as much as we ever find out, though. Fairy tales are notorious for the shallowness of their character descriptions, but this story really takes that fact to a whole new level. We know she’s beautiful, good, can sing, and is desperately lonely in her tower, but that is the most we ever learn about her (6).

One thing we can deduce is that her singing is an important and special characteristic. For one thing, it is what draws the prince to her and essentially leads to her eventual freedom. For another, singing is the one talent given to her other than her physical beauty. At the time this tale was recorded, there was no such thing as recorded sound and live music, something that was a common part of an evening’s entertainment, often required a talented singer. This sets Rapunzel apart, as people with beautiful singing voices were often prized and held in high esteem (2).

However, her lack of intelligence is pointed out a few times. It is not Rapunzel but the prince who suggests her escape, placing her firmly in the category of the passive fairy tale heroine, letting others do the thinking for her. Her first major blunder, however, is when she gives away the fact that she is planning on running away with the prince when she asks one night why Mother Gothel is so much harder to pull up into the tower than the prince. She’s clearly not the sharpest tool in the shed. Later on in the story, when Mother Gothel has the prince in her clutches, she tells him that “the beautiful bird is no longer sitting in the nest, singing her songs.” The comparison of Rapunzel to a caged songbird suggests a simple and somewhat vapid quality in her. Especially when paired with the rest of the metaphor, in which Mother Gothel places herself in the role of the cunning cat who caught her (2). Yeah…I’m starting to think the Grimm’s were making their own jab at dumb blondes.

Disney’s adaptation gives Rapunzel quite a makeover. She’s still the same beautiful damsel in distress with those luscious long locks of golden hair and a voice like a siren, but that’s where the similarities end. Mandy Moore, the voice behind the picture, thinks of Rapunzel as “a bohemian Disney princess. She’s barefoot and living in a tower. She paints and reads…She’s a Renaissance woman.” Moore goes on to say in another interview that “She’s not the typical femme fatale or the typical Disney princess…she’s just really sort of motivated to find out what else is out there beyond this crazy tower she’s lived in for 18 years. Having said that, she’s very independent, she can take care of herself, and she’s definitely come up with really entertaining ways to keep herself busy (7, 8).” Glen Keane, executive producer and an animating director of Tangled, revealed his fascination with the idea of a “girl with this incredible potential being kept back (9).”

We first see this new and more independent nature when the film reveals that Rapunzel is fascinated with the lanterns that she sees in the sky every year on her birthday. Her motivation for leaving the tower is to find these lanterns that she feels a connection with. This is already a big change in character, as it suggests a greater degree of innate independence. Rapunzel has already considered and wants to leave the tower because of her desires not because of someone else’s. Escape hadn’t even occurred to the Grimm’s Rapunzel until the prince came into the story. To build upon this, Rapunzel is then the one who devises the ruse she tells to Mother Gothel to get her to leave for three days, thereby giving Rapunzel the chance to escape. To top it off, she figures out how to manipulate this version’s “prince,” the thief Flynn Rider, into helping her escape and find the lanterns. Rapunzel is the mastermind and instigator of every momentous action she has chosen to take so far. For someone who’s been locked in a tower for eighteen years, she’s a quick study.

In the original Grimm tale, Rapunzel’s journey after she leaves the tower is glossed over. We are simply left to assume that Rapunzel has finally matured into an adult woman when she reunites with her prince at the end of the story. Disney, however, makes it the focus of the entire film. In both versions, Rapunzel’s escape from the tower is seen as a symbol of her maturation into womanhood. To do this, Rapunzel must integrate the masculine side of sexuality with the feminine. She has to leave the tower, a solely feminine sanctuary (a completely contained world where she sings while performing a full range of stereotypically female domestic duties) and experience the masculine, which she does through her interactions with Flynn Rider.

The Prince and The Thief

Not only does Disney reinvent the figure of Rapunzel, but the prince as well, making him into an active participant in Rapunzel’s journey outside the tower. The figure of the prince may convince Rapunzel to leave, but after she is gone and he escapes the enchantress, his active participation in Rapunzel’s life goes no farther than him “weeping and wailing over the loss of his dear wife” (2). He’s pretty useless as far as heroes go, never making any active attempt to find her. Only by chance do they meet up again after an extended period of time.

The first outcome of Disney’s reinterpretation of the prince figure is that he affects Rapunzel’s journey and influences her development into an adult. Rapunzel, in turn, influences Flynn, transforming our “prince” into a fully realized character who goes through changes alongside Rapunzel. Another result of changing the male figure in the story is the effect this has on the dynamic between the pair, which will change the manner of their interactions, and ultimately the nature of the very relationship between the romantic pair. The story is no longer solely about a princess being rescued from her tower by a two-dimensional prince. The story is now about the development of both characters. Rapunzel now shares the spotlight with Flynn.

The choice to make Disney’s new prince into a thief was a careful one. Flynn Rider is a decidedly more colorful character than the original prince. Rather than present Rapunzel with someone safe, Disney wanted to challenge her with a figure that embodied all of Mother Gothel’s warnings about the danger that lurked outside the tower walls. Rapunzel lets in the exact kind of shady character her mother was worried about (9). Not only does this make the story more interesting, it also helps to highlight Rapunzel’s bravery and independence. Producer Roy Conli revealed that “In our film, the infamous bandit Flynn Rider meets his match in the girl with the 70 feet of magical golden hair. We’re having a lot of fun pairing Flynn, who’s seen it all, with Rapunzel, who’s been locked away in a tower for 18 years” (10). It’s a case of the charming rogue versus the feisty teen.

As we follow the pair throughout their journey to find Rapunzel’s lanterns, we see how both characters influence and change each other. For Rapunzel, Flynn serves as a guide to the outside world, helping her navigate the unfamiliar waters of life outside the tower. When Rapunzel first leaves the tower she is immediately thrown into intense conflicting feelings about her actions. Without Flynn the story could have ended right there. He is the one who encourages her to embrace the adventure, telling her that a little rebellion is good and normal. I’d say this marks one of Rapunzel’s first steps towards adulthood and separating from her overbearing mother.

Disney’s choice to have Flynn narrate the story is an interesting one. This implies he will be an important player in this tale from the very beginning. In fact, Flynn ends up being an important catalyst at several points in Rapunzel’s journey, one of them being the above scene. Another one is when Flynn takes her to the Snuggly Duckling. Rapunzel is forced to deal with her fear of the thugs and figure out how to adapt to meeting new people from the outside world and find a way to try and relate to and fit in with them. We also start to see Rapunzel begin to inspire a change in Flynn (among other people). Glen Keane admitted to Disney’s desire to highlight Rapunzel’s unique gift with people. “We were looking for ways that Rapunzel could show the transforming power that she has with the horse, with the thugs in the pub, with the people in the town that she gets to dance with her, and ultimately with Flynn himself” (9).

Flynn and Rapunzel’s journey culminates in a scene strikingly similar to the end of the Grimm’s version. Rapunzel and Flynn have reached the end of their journey, defeating Mother Gothel and finding Rapunzel’s birth parents. Just as they have achieved the ultimate goal of reaching their full potential as mature adults, and realized their romantic feelings for each other, Eugene makes the ultimate sacrifice and gives up his life for Rapunzel’s freedom. However, just when it seems all hope is gone, a single tear from Rapunzel lands on Eugene, miraculously bringing him back to life.

Similarly, in the Grimm’s version when Rapunzel and her prince have finally found each other after their long separation, Rapunzel’s tears restore the prince’s sight (2). And so everything comes full circle. Both stories begin with a princess locked in a tower and end with their love healing the hero and allowing them to live happily ever after. The thing to remember, however, is the importance of the journey. At the end of the day, that is what Disney gave to this modern take on an old tale. The tales may begin and end the same, but it’s the journey and the characters that struggle through it that brings life and meaning to this iconic fairy tale. One might even say that the moral applies to our own lives. It’s ultimately the journey and the people you travel with that counts.

References:

1. “Tangled (2010)”. Box Office Mojo.

2. Ed. by Maria Tatar. The Annotated Brothers Grimm. W. W. Norton & Company; The Bicentennial Edition edition (October 15, 2012)

3. Corliss, Richard (November 26, 2010). “Tangled”: Disney’s Ripping Rapunzel.” Time.

4. Scott, A.O. (November 23, 2010). “Back to the Castle, Where It’s All About the Hair”. The New York Times.

5. “‘Tangled’ directors unravel film’s secrets”. SiouxCityJournal.com. December 5, 2010.

6. Maria Tatar. The Hard Facts of the Grimms’ Fairy Tales (Expanded Second Edition). Princeton University Press; Expanded edition (May 26, 2003)

7. “Mandy Moore On Tangled: ‘I Screamed As Soon As I Found Out’ (INTERVIEW)”. The Huffington Post UK (HuffPost Entertainment). October 19, 2011.

8. Warner, Kara (August 27, 2010). “Mandy Moore’s ‘Tangled’ Heroine Not ‘Typical Disney Princess’”. MTV News (Viacom International Inc.).

9. Minow, Nell. “Interview: Glen Keane of ‘Tangled’”. Beliefnet. Beliefnet, Inc.

10. Dawn C. Chmielewski; Claudia Eller (March 9, 2010). “Disney restyles ‘Rapunzel’ to appeal to boys”. Los Angeles Times.

ARE YOU A ROMANCE FAN? FOLLOW THE SILVER PETTICOAT REVIEW:

Our romance-themed entertainment site is on a mission to help you find the best period dramas, romance movies, TV shows, and books. Other topics include Jane Austen, Classic Hollywood, TV Couples, Fairy Tales, Romantic Living, Romanticism, and more. We’re damsels not in distress fighting for the all-new optimistic Romantic Revolution. Join us and subscribe. For more information, see our About, Old-Fashioned Romance 101, Modern Romanticism 101, and Romantic Living 101.

Our romance-themed entertainment site is on a mission to help you find the best period dramas, romance movies, TV shows, and books. Other topics include Jane Austen, Classic Hollywood, TV Couples, Fairy Tales, Romantic Living, Romanticism, and more. We’re damsels not in distress fighting for the all-new optimistic Romantic Revolution. Join us and subscribe. For more information, see our About, Old-Fashioned Romance 101, Modern Romanticism 101, and Romantic Living 101.

Comments are closed.